Farewell - Adagio from Symphony No. 10

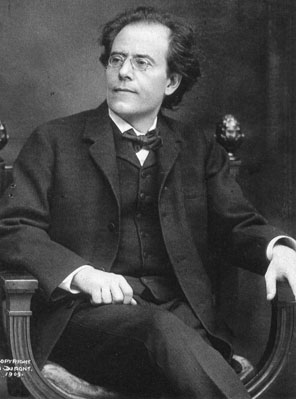

A Timeline of Mahler's Music

Although some of the ideas for his Symphony No. 10 go back to 1908, Mahler did most of the work on this unfinished score in the summer of 1910. The first attempt at preparing a practical full score was undertaken by the composer Ernst Krenek in 1924. He presented the first and third movements only, and these sections were performed on October 14, 1924 by Franz Schalk and the Vienna Philharmonic.

The score for the Adagio calls for three flutes (third doubling piccolo), three oboes, three clarinets, three bassoons, four horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tuba, harp, and strings.

These notes are used by kind permission of the estate of Michael Steinberg and are taken from the complete notes in his Oxford volume “The Symphony”.

When Bruno Walter conducted the posthumous premieres of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde in Munich in November 1911 and the Symphony No. 9 in Vienna in June 1912, it seemed that all of Mahler’s music had been offered to the public. It was assumed that the Tenth Symphony was in too fragmentary a state ever to be performed, and word went about that Mahler had asked his wife to destroy whatever drafts remained.

In 1912, Arnold Schoenberg, that paradoxical confluence of the rational and the mystic, wrote: “We shall know as little about what [Mahler’s] Tenth . . . would have said as we know about Beethoven’s Tenth or Bruckner’s. It seems that the Ninth is a limit. He who wants to go beyond it must die. It seems as if something might be imparted to us in the Tenth which we ought not yet to know, for we are not yet ready. Those who have written a Ninth stood too near the hereafter. Perhaps the riddles of this world would be solved if one of those who knew them were to write a Tenth. And that is probably not going to happen.”

Mahler, for that matter, had his own misgivings about going beyond the Ninth. He had called Das Lied von der Erde a symphony without numbering it, so that the symphony he called No. 9 was actually his tenth. Thus he had dealt with “the limit” by circumvention, or so he believed. With ten symphonies completed (counting Das Lied von der Erde), Mahler moved virtually without pause from the last pages of the official No. 9 to the first of No. 10. In 1911, the discovery of penicillin was still seventeen years away. Had that antibiotic been available to combat his blood infection, there is little doubt he would have finished his work-in-progress that summer.

Schoenberg did not know how far Mahler had actually progressed on his Tenth. Only Mahler’s widow had any idea until 1924, when she asked the twenty-three-year-old composer Ernst Krenek to “complete” the symphony. Krenek felt this to be an “obviously impossible” assignment, but he prepared a practical full score of two movements, the Adagio, which was complete, and Purgatorio, which was nearly complete. At the same time, Alma Mahler Gropius, as she then was, allowed the Viennese publisher Paul Zsolnay to publish a large part of Mahler’s manuscript in facsimile. Her decision was surprising.

Gustav Mahler, in 1910, was a man in torment, for he believed himself on the point of losing his intensely beloved, much younger, beguilingly beautiful wife. Alma Maria Schindler met Mahler in November 1901, became pregnant, and married him four months later. Their devotion was mutual and passionate, but they were fundamentally out of tune. Eight years into their marriage, Alma, flirtatious by temperament and frustrated by Gustav’s sexual withdrawal from her, was restless. In May 1910, she met Walter Gropius, four years her junior and about to embark on one of the most distinguished careers in the history of architecture. Under trying and even bizarre circumstances—Gropius had by accident (!) addressed the letter in which he invited Alma to leave Gustav to “Herr Direktor Mahler”—Alma chose to stay with her husband, who later told her that if she had left him then, “I would simply have gone out, like a torch deprived of air.” Through the score of the Tenth Symphony, Mahler scribbled verbal exclamations that reflect this crisis, and it cannot have been easy for Alma to agree to the publication of such painfully intimate material. The so-called Krenek edition of the Adagio and Purgatorio, long the only available performing edition of any music from the Tenth Symphony, lacked too much both of science and art to be satisfactory. In 1959 the English musician and writer Deryck Cooke began work on what he called a “performing version” of all five movements. This was introduced in 1964 and revised in 1976. With the appearance of the Adagio in the critical Mahler edition and of Deryck Cooke’s second “performing version,” the Krenek edition has for all intents and purposes dropped out of circulation.

Some considerable voices, including those of Bruno Walter, Leonard Bernstein, Rafael Kubelík, and Pierre Boulez, have spoken out against the “complete” Mahler Tenth, and Cooke himself would never have taken the position that his version was the last word. All this is background to a performance of music that Mahler did complete, the Adagio we hear now.

In the Tenth Symphony, Mahler returned to the symmetrical five-movement design he had used in his Fifth and Seventh symphonies and in the original version of the First Symphony. This idea was not clear to Mahler to begin with, and he changed his mind more than once about their order within the whole. He called his first movement an “Adagio,” but he does not enter that tempo until measure 16. He begins, rather, with one of the world’s great upbeats: a pianissimo Andante for the violas alone, probing, wandering, surprising, shedding a muted light on many harmonic regions, slowing almost to a halt, finally and unexpectedly opening the gates to the Adagio proper. This is a melody of wide range and great intensity—piano, but warm, is Mahler’s instruction to the violins—enriched by counterpoint from the violas and horn, becoming a duet with the second violins, returning eventually to the world of the opening music.

These two tempi and characters comprise the material for this movement. A dramatic dislocation, with sustained brass chords and sweeping broken-chord figurations in strings and harp, brings about a crisis, the trumpet screaming a long high A, the orchestra seeking to suffocate it in a terrifying series of massively dense and dissonant chords. Fragments and reminiscences, finally an immensely spacious, gloriously scored cadence, bring the music to a close.

— Michael Steinberg