Mahler used a variety of techniques to achieve his parodic quality. He inserted passages completely at odds with existing material, he twisted the elements of melody or harmony to render the familiar unfamiliar, and he allowed different lines to pile up in unpredictable collisions.

-

In the Scherzo of the Fourth Symphony, as if to portray the Devil in the form of a village musician playing his rough fiddle, Mahler asks the concertmaster to tune his violin a tone higher than usual. A soloist in a playful chamber instrumentation, he plays a tune in C minor which perversely returns again and again to the alien note F#: the tritone, “the devil in music.” As a result of the special tuning, this note is played on an open string with a swell in the sound, suggesting a ghostly moan or cry.

Play

Play

At one grotesque point in the Scherzo of the Seventh Symphony, the cellos and basses dispense with pitches altogether.

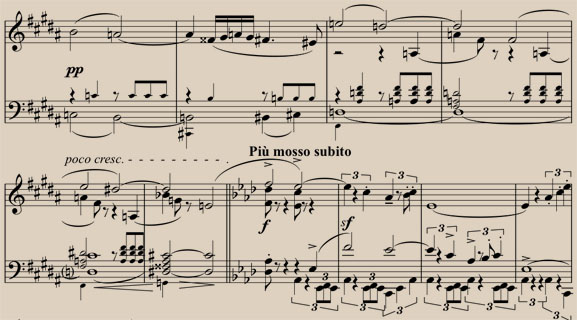

As the energy of the Rondo-Burlesque reaches its crazed climax, Mahler drops in snatches of famous marches of the Empire often used for celebrations and festivals:

-

He tosses whole phrases of Strauss’s iconic Radetzky March into his musical stew.

-

As director of the Vienna Opera, Mahler refused to stage a second-rate opera based on the life Hungarian patriot Rákóczy. So it’s only fitting that he also threw in fragments of the infamous Rákóczy March.

-

Screaming above the orchestral maelstrom, they seem to tease and taunt (In the score extract shown here, the Radetzky March is highlighted by orange notes, the Rákóczy by blue). Did the intrigue and spite that eventually played a part in Mahler leaving the Vienna Opera find an ironic reflection here?