Mahler’s music pays tribute to his predecessors in the classical canon through quotation, imitation, and evocation.

All composers of the late 19th century felt an indebtedness to Beethoven and his nine symphonies. Here, in the opening to the First Symphony, Mahler even seems to draw attention to the fact that he’s standing on Beethoven’s shoulders.

-

The funeral march from Donizetti’s opera Dom Sebastien was as famous in the nineteenth century as Chopin’s Funeral March, and was certainly familiar to Mahler from military ceremonies in Iglau. The young Mahler also performed Liszt’s transcription for piano of this same march at a childhood recital.

-

It must have haunted him down the years, because he quoted the march’s major-minor harmonies in the last of his Songs of a Wayfarer (Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen). The narrator sings of loneliness and isolation to the cadences of a funeral march: “I went out into the quiet night, over the dark meadow. No one bade me farewell.” A few years later, he transposed some of this song to a section of the First Symphony’s slow movement.

Mahler’s Fifth Symphony makes obsessive use of the “fate” motive of Beethoven’s Fifth.

-

Initially it’s a motif of gentle urgency (and also an inversion of the piece’s opening fanfare) that accompanies the most intimate music of the first movement.

-

In the second movement, the same music returns in a shriller orchestration, sounding like a mocking laugh or an accusing cry.

-

Mahler intended his Adagietto as a declaration of love to his wife Alma.

-

One ardent passage makes an affectionate reference to the main love motive of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde.

-

Then as a farcical touch in the last movement the passage is revisited at a much faster speed. Gustav and Alma dance the polka!

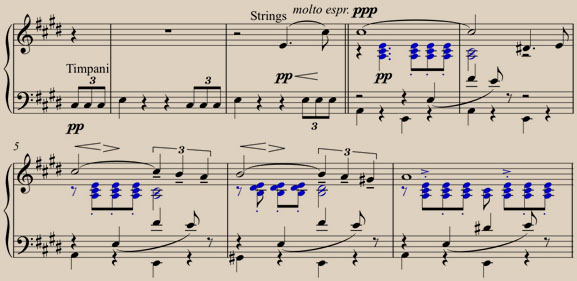

Mahler called Anton Bruckner his “forerunner”. In the use of the Ländler in his colossal slow movements, and even in his transitions between keys, the elder Austrian composer foreshadowed several of the musical and aesthetic preoccupations of the younger one. Here are extracts from the slow movements of the Sixth Symphonies of both composers.