Although he never reduced music to words, they were a clear source of inspiration. He loved reading poetry and philosophy, and the words and ideas influenced all aspects of his music.

-

Scary and spooky folk tales were an important thread in Mahler”s childhood experience. His first large-scale work, Song of Sorrow (Das Klagende Lied), is based on a story of a man who kills his brother, only to be confronted at his own wedding by the accusing voice of the dead man sounding from a flute made of bone: "A miracle, what now began, what strange and sorrowful singing! It sounds so sad and yet so beautiful. Whoever hears it wants to lose himself in sorrow! Oh sorrow, sorrow!"

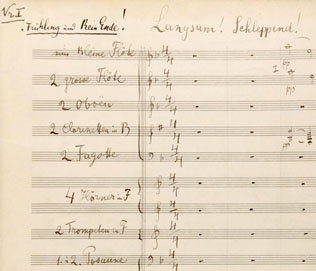

Both Mahler’s First and Second Symphonies raise the question of whether Mahler intended his music to have particular extra-musical meanings. Throughout his life, Mahler struggled with whether and how to explain his music to the public. He originally named his First Symphony the Titan, and gave the movements the following titles:

—Spring without end

—A chapter of flowers

—With full sails

—Stranded! A funeral march in the manner of Callot

—From hell to heaven, as the sudden expression of a deeply wounded heart.

By the time of the music’s publication in 1898, he had withdrawn the second movement as well as these titles. Yet he returned to explanation in the Second Symphony, expounding his concept that the hero of the First Symphony is borne to his grave in the funeral music of the Second and that “the real, the climactic dénouement [of the First] comes only in the Second.”

In spite of Mahler's frequent extra-musical references, he was leery of assigning a specific "program" to his music. About the titles he originally gave the movements of his Third Symphony, he wrote: “Those titles were an attempt on my part to provide non-musicians with something to hold on to and with a signpost for the intellectual, or better, the expressive content of the various movements and for their relationships to each other and to the whole. That it didn’t work (as, in fact, it could never work) and that it led only to misinterpretations of the most horrendous sort became painfully clear all too quickly. It’s the same disaster that had overtaken me on previous and similar occasions, and now I have once and for all given up commenting, analyzing all such expediencies of whatever sort.”

Play

Play

Mahler turned to the poetry of Friedrich Rückert (1788 - 1866) for two important song collections: Songs on the Deaths of Children (Kindertotenlieder)and the five settings collectively titled simply Rückert Songs (Rückert-Lieder). Mahler felt a deep aesthetic kinship with the poet's imaginative and imagistic vocabulary, moreover, both artists were attracted to Oriental sources. Mahler himself had written a student essay on the influence of the Orient on German literature and later turned to Chinese poetry for his last great song-symphony The Song of the Earth (Das Lied von der Erde).

-

The second part of the Eighth Symphony follows line by line one of the most famous poems in German literature, the last scene of Goethe’s Faust. Mahler’s revels in the power of music to suggest Goethe’s mystical stage directions, such as Pater Estaticus, auf und ab schwebend (soaring up and down).